When the New York Times editorial board sat down to interview Elizabeth Warren, the first question was about Hunter Biden. These 17 distinguished journalists proceeded to fire a bunch of zingers at the candidate, seeing if they could trip her up on hot button issues like immigration, trade, and Medicare for All. The transcript is about as thought provoking and inspiring as the end result – the Times’s lily-livered dual endorsement of both Warren and Amy Klobuchar.

During the interview Warren struggled to interject a discussion of her central campaign issue – ending political corruption in America. But the board members didn’t seem to think that Warren’s defining policy priority deserved much more than passing attention.

Given that we have a president who is a reality show Caligula, and that we live in an era defined by the blatant, unrepentant and unrestrained corruption of his Administration, you would think that “corruption” would be a meaty enough topic to warrant a bit of a back and forth.

Unfortunately, the Times is not alone in its skirting of the issues related to corruptive role of money and influence in our politics, government and economy. Although Bernie Sanders and Warren have put the fight against corruption at the center of their campaigns, Sanders’ more raw form of “us against them left wing” populism has, it seems for now, played better than Warren’s more fully sketched out set of proposals for fundamental reforms. It’s telling that while Sanders and Warren both took the high road of declining large contributions and PAC financing, Biden, Buttigieg and others didn’t make the same choice, and don’t seem to be taking much heat as a result.

The news media — including pundits and the polling establishment — are partly to blame for the weak and diffuse impact of the political reform issue. Journalists intermittently focus on issues related to corruption – coverage spikes when there’s scandal, and a small core of reporters does ongoing investigative work on PACs, lobbying and the revolving door. There’s a dedicated and effective network of public interest research groups that focus on money in politics, particularly Open Secrets, the Sunlight Foundation, and their research often provides the data used by journalists investigating money in politics stories. The do gooders keep at it but work mostly on the margins.

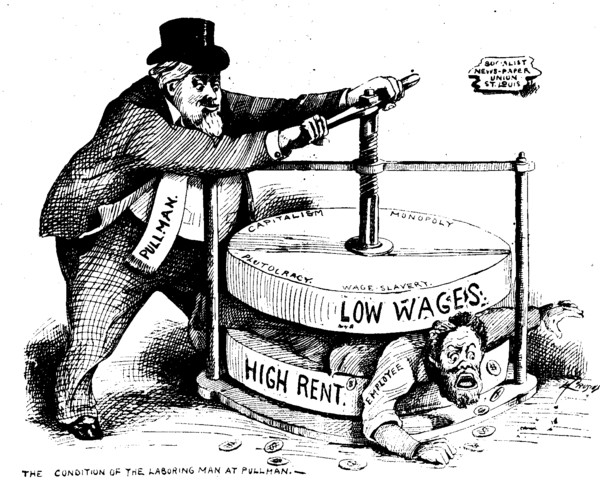

The role of the news media is crucial – and so far, we have found no equivalent of the Muckrakers who played such an important in building public support for the reforms of the Progressive Era. One slightly paranoid explanation is that our news media is deeply embedded in the system of corruption, and thus they are less likely to persistently expose it. Reporters and editors are not explicitly on the take, but they are part of a Washington establishment that has normalized the nexus of K-Street lobbying, PACs, the role of money in Congressional and Presidential politics, and the revolving door between government, lobbying, big law and Wall Street. Even the most inspired and impassioned journalist would have a tough time rising against the bigger trends in the business: most news outlets are owned by larger corporations, the newspaper industry bleeds out and news via click bait and Facebook creates an environment that is hardly conducive to long from investigative reporting.

There’s an even more depressing explanation of why the bad guys are getting away with it: voters probably don’t care that much about corruption. Corruption doesn’t generate clicks, and therefore covering it becomes a lower priority. Following the money may be good for an occasional Pulitzer Prize or investigative journalism award, but it doesn’t pay for the news media to devote resources to fully and persistently cover an issue that inspires apathy in an audience. The public prefers to follow the gladiatorial aspect of partisan political combat but has little interest in investigative reporting about how money has “captured” their government.

Opinion research does in fact suggest that while ‘corruption” concerns many voters, it is not a consistently dominant concern. In Gallup’s most recent poll of the most important 2020 issues, 35% ranked healthcare as extremely important – terrorism and national security, gun policy, education and the economy all polled over 30%. “Corruption” was not on Gallup’s list of issue prompts – and also doesn’t enter into other influential polls ranking issues.

Opinion researchers have to dig a bit deeper to surface concerns about corruption. At the top level, as an overlay to any public concern about corruption, is a widespread lack of trust and confidence in the government. One well known index of trust hit an all-time low of 17% in 2016, with a record-breaking 82% believing that government is run for the benefits of a “few big interests.” And within that total collapse of trust, are indications that the public is in fact angry about issues that fall within the realm of corruption. In one poll, 43% of the respondents said “I feel angry because our political system seems to only be working for the insiders with money and power.” A NY Times poll found that 84% of Americans thought money has too much influence on campaigns and 55% believed that candidates directly help donors “most of the time.” Going back to 2010, with the financial crisis and bailouts still fairly raw, half the public reported that they “frequently” talk about corruption in government.

Yet while lack of trust and anger about corruption lurk in the background as a public concern, fostering cynicism and disgust, it doesn’t stay at the forefront. And I would argue that a major reason that corruption hasn’t defined the political conversation is that the nature of corruption is too deep and complex to lend itself to sound bites.

Corruption effects the economy and the society in many ways that are blatant, but in many other ways that are concealed and hard to grasp. The overt role of money in politics, including campaign contributions, PACs, dark money, lobbying and the revolving door all can be understood from a basic transactional framework: I pay you, and you promote legislation, executive decisions, regulatory policies and judicial decisions that benefit my interests. Certainly, the system is not dominated by a single interest group or ideology; there is competition for influence, Soros v. the Kochs, Bloomberg v. Adelson, that works to even things out.

But the system is definitely “rigged.” The deeper and more pervasive corruption also works to benefit entrenched interests at the expense of the public interest. In the economy, large and established companies are favored over smaller competitors, which has led to a sharp increase in industrial concentration, a decline in competition and an increase in profits. In some very significant ways – such as the failure to enforce antitrust law — inaction has played the key role in favoring entrenched interests, and inaction is a force that’s difficult to measure or push back against. It’s made the economy less dynamic and tended to raise prices and to suppress wage and income growth. Government and regulatory agencies are “captured” by special interests, tilting the balance in favor of the entrenched and the elite.

Economists have another word to explain how the system gets rigged – rent seeking. “Rent” describes economic benefits that accrue an interest group that go beyond what it would receive if the political system and the economy were competitive rather than skewed in the interest group’s favor. “I think that people getting rich is a good thing, especially when it brings prosperity to others,” says Nobel Laureate Angus Deaton said in a 2019 speech. “But the other kind of getting rich, “taking” rather than “making,” rent-seeking rather than creating, enriching the few at the expense of the many, taking the free out of free markets, is making a mockery of democracy. In that world, inequality and misery are intimate companions.” He continued: “ In the face of globalization and innovation, many of us would argue that American policy, instead of cushioning working people, has instead contributed to making their lives worse, by allowing more rent-seeking, reducing the share of labor, undermining pay and working conditions, and changing the legal framework in ways that favor business over workers.”

Corruption (i.e. rent seeking) sharply inflates pharmaceutical prices and health care costs. It allows multinational corporations to game the tax laws and shelter profits in overseas tax havens. And it has enabled the rise of the tech company leviathans.

Yet corruption hasn’t brought down Trump. And it doesn’t seem to be central to the political conversation as the Democratic campaign finally starts to get real. Warren staked her campaign on the issue but hasn’t yet found the rhetorical force to build a sustained movement around the issue of reform. Sanders has capitalized on the issue, but in his own endearingly demagogic populistic style.